What are Circular Oligonucleotides?

Circular oligonucleotides are covalently closed singular DNA or RNA strands that are resistant to degradation by many cellular DNA and RNA decay machineries.

Models of circular DNA and RNA

[Figures were adapted from: Modelling DNA Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A-2006-Harris-3319-34; David Goodsell at http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/101/motm.do?momID=65: The self-splicing RNA in PDB entry 1u6b caught in the middle of its splicing reaction is illustrated].

Circular DNA

Modern biology focuses on the study of molecules within cells as well as the interaction between cells to understand and describe multi-cellular organisms most of which are visible to a human’s eye. Molecular cell biology concentrates on the study of macromolecules, such as carbohydrates, DNA, polypeptides, proteins, RNA, lipids as well as others, their biochemistry and processes that regulate metabolic pathways in these organisms.

Mitochondria and chloroplasts found in today’s eukaryotes contain circular DNAs encoding proteins. These proteins are essential for the function of organelles and the ribosomal and transfer RNAs required for their translation.

Eukaryotic cells have multiple genetic systems:

(1) a nuclear system, and

(2) systems with their own DNA present in mitochondria and chloroplasts.

Human mitochondrial DNA, mtDNA, is a circular DNA molecule which sequence is now completely known. This human mtDNA is among the smallest known mtDNAs. The circular mtDNA molecule is a compact, double-stranded circular genome contains 16,569 base pairs that encode two ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs). These are present in mitochondrial ribosomes and 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs) needed to translate mitochondrial messenger RNAs (mRNAs). In addition, human mtDNA contains 13 sequences that begin with the ATG (methionine) codon and end with a stop codon. These DNA sequence stretches are long enough to encode polypeptides of more than 50 amino acids. All of the possible proteins encoded by these open reading frames have now been identified. Mammalian mtDNA has no introns and contains no long noncoding sequences. A single cell can have several hundred to thousands of copies of the circular mitochondrial genome.

Since the 1970s scientists have known that, bacteriophages contain circular DNA. For example, Arnberg et al. in 1976 reported that a DNA-protein complex contains circular DNA in the bacillus bacteriophage GA-1. In addition, the researchers found that proteins are bound to DNA purified from bacillus bacteriophage GA-1. The removal of DNA-associated proteins by treatment with proteolytic enzymes resulted in

(i) a loss of transfecting activity of GA-1 DNA on competent Bacillus subtilis cells and

(ii) an increase (0.004 g/cm3) in the buoyant density of the DNA.

GA-1 DNA, when analyzed by electron microscopy appeared as 6.4-µm-long circular and linear molecules. The analysis of 170 DNA molecules in the untreated GA-1 DNA preparation found 30 (18%) to be circular oligonucleotides. However, no circular molecules among 500 molecules analyzed were observed in trypsin-treated DNA. The researchers concluded that proteins are responsible for the circularization of GA-1 DNA.

Since the 1990’s researchers have set out to synthesize and study circular DNA constructs. For example, Prakash and Kool reported in 1992 the synthesis of circular DNA oligomers ranging in sizes from 24 to 46 nucleotides. In addition, the scientist reported that oligomers containing four, eight, twelve, and eighteen nucleotides can form strong complexes with these circular DNA. The melting temperatures (Tm) of these complexes were observed to be 17 to >33 °C higher than the ones for the corresponding Watson-Crick duplexes of the same length. In addition, melting temperature studies confirmed that the circular DNAs can bind to complementary sites within longer oligonucleotides. These data indicated that circular DNA molecules can act as hosts for molecular recognition and form a triple helix with single-stranded nucleic acids.

Chen and Ruffner in 1998 reported that an in vitro procedure called ligation-during-amplification (LDA) can be used for the selective amplification of closed circular DNA using sequence-specific primers. Their report showed that LDA is a useful technique for site-directed mutagenesis, mutation detection, DNA modification, DNA library screening and the production of circular DNA. Scientists now know that triple helix formation can be used for the recognition of single-stranded DNA or RNA. Oligonucleotides that were designed to form intermolecular parallel triple helixes at a polypyrimidine RNA sequence stretch were shown to arrest protein synthesis from that RNA template in a cell-free system. Other types of circular oligonucleotides were synthesized in recent years either using chemical or biological ligation. These circular oligonucleotides can also form a triple helix with single-stranded nucleic acid displaying higher mismatch discrimination for its complement as compared to normal DNA duplexes. Detailed kinetic studies showed that the rates of triple helix formation by circular oligonucleotides were approximately 100 times faster than that for normal triple helix formation.

Circular RNA

Circular ribonucleic acids (RNAs) are part of a newly revealed previously unexplored hidden world.

Over the last 20 years may forms of RNAs have been discovered, some of them were unexpected. What made these discoveries possible? Most RNA sequencing methods detect molecules that contain tails. The old sequencing methods did not allow detecting and analyzing circular RNA molecules. However, newer sequencing methods now are revealing the presence of these molecules in many organisms such as humans, mice and worms.Furthermore, recent research indicates that circRNA molecules may be more abundant than what we previously thought. For example, the RNA genome of the hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a single-stranded, negative sense, small circular RNA molecule containing approximately 1700 nucleotides. This circular, covalently closed RNA strand is rod-shaped because of extensive base pairing. The HDV genome is surrounded by the d antigen core encoded by HDV that is subsequently encased in an envelope embedded with Hepatitis B antigens (HBsAg) or virus envelope proteins. Circular transcripts were observed in rodents 20 years ago. For example, the mouse SRY gene consists of a single exon. This gene determines the sex in male rodents. During the development of the animal, the RNA exists as a linear transcript that is translated into protein. However, in the adult testes the RNA exists primarily as a circular product predominantly localized to the cytoplasm and apparently not translated. It has been found that inverted repeats in the genomic sequence flanking the SRY exon direct transcript circularization.

Recently a new class of circRNAs has been reported to be abundant in mammalian cells. These circular RNAs are an enigmatic class of RNA with unknown function. However, emerging data indicate that these RNAs appear to regulate microRNAs (miRNAs). In recent years high-throughput sequencing has identified a large number of distinct RNAs generated from non-protein-coding regions of the genome. These noncoding RNAs can vary in length and like protein-coding RNAs appear to be linear molecules containing 5’ and 3’ termini.

Wang and Kool in 1994 reported the synthesis and nucleic acid binding properties of two cyclic RNA oligonucleotides. These RNA molecules were designed to bind single-stranded nucleic acids by pyrimidine.purine.pyrimidine-type (pyr.pur.pyr-type) triple helix formation. The circular RNAs containing 34 nucleotides were cyclized employing a template-directed nonenzymatic ligation method. One nucleotide at the ligation site was a 2'-deoxyribose. These nucleotides was selected to ensure isomeric 3'-5' purity during the ligation reaction. One circular molecule was complementary to the sequence 5'-A12, and the second was complementary to the sequence 5'-AAGAAAGAAAAG. The researchers performed thermal denaturing experiments to show that both circular RNA molecules bind to complementary single-stranded DNA or RNA substrates by triple helix formation. According to the reported results two domains in a pyrimidine-rich circular RNA molecule sandwich a central purine-rich substrate. In addition, the measured affinities of these circular RNAs with their purine complements were much higher than the affinities of either the linear precursors or simple Watson-Crick DNA complements. The comparison of circular RNAs with previously synthesized circular DNA oligonucleotides of the same sequence showed that they were similar in binding to DNA, but very different in the binding behavior towards RNA. The relative order of thermodynamic stability for the four types of triplex studied were found to be DDD >> RRR > RDR >> DRD. The researchers argued that triplex-forming circular RNAs represent a novel and potentially useful strategy for high-affinity binding of RNA.

Wilusz and Sharp in 2013 (Science 26 April 2013) report that circular RNAs have covalently linked ends and are found in pathogens such as viroids, circular satellite viruses, and hepatitis B.

Viroids are small, circular, single-stranded RNAs that cause several infectious plant diseases. The RNA genome of the viroids contains functional motifs that allowing them to spread in the plant by recruiting host proteins. Many of these circular RNAs are thought to replicate by a rolling-circle-based mechanism.

In addition, a few circular RNAs generated from eukaryotic genomes have also been identified. However, until recently their exact role in the cells was unclear. The scientists report in this paper that a new method that combines high-throughput sequencing data with a new computational algorithms has recently revealed thousands of circular RNAs in a wide range of species ranging from humans to archaea. In addition, it was observed that human fibroblasts alone have more than 25,000 circular RNAs. These circular RNAs are derived from approximately 15% of actively transcribed genes, apparently mostly from exonic sequences. Large numbers of these RNAs accumulate in the cytoplasm of cells and sometimes exceed the abundance of associated linear mRNA by a factor of 10.

Fibroblasts are cells that synthesize the extracellular matrix and collagen as part of the structural framework of animal tissues. In addition, these cells play a critical role in wound healing and are the most common cells of connective tissue in animals.

Circular RNAs are resistant to degradation by many cellular RNA decay machineries since these recognize the ends of linear RNAs to function. The identification of a subset of these circular RNAs in humans and mice indicates that the circularization signals are evolutionarily conserved. It is hypothesized that the splicing machinery is involved in their biogenesis. However, the exact mechanism, how this works, will need to be elucidated in the future.

Salzman et al. in 2012 report their deep-sequencing results of normal and malignant cells that showed that RNA transcripts from exons in many human genes were arranged in a non-canonical order. The analysis of these transcripts with statistical and biochemical assays provided strong evidence that different modes of RNA splicing resulted in circular RNAs. Their results suggest that many eukaryotic RNAs exist in a circular form that may be part of a general feature of the gene expression program. The researchers proposed models to explain how these circular RNAs are formed. One model attempts to explain the mechanism of exon scrambling and the others to explain circle splicing.

Memczak et al. recently sequenced and computationally analyzed human, mouse and nematode RNA. The research group detected thousands of well-expressed, stable circRNAs. Their sequence data and analysis indicated that the circRNAs showed tissue-developmental-stage-specific expression and that these RNAs may have important regulatory functions. Furthermore, the researchers report that a human circRNA that is antisense to the cerebellar degeneration-related protein 1 transcript (CDR1as) is densely bound by microRNA (miRNA) effector complexes and contains 63 conserved binding sites for the ancient miRNA miR-7. In summary, the researchers data provided evidence that circRNas form a large class of post-transcriptional regulators and that numerous circRNA form by head-to-tail splicing of exons. The researcher argue that their data support the notion that animal genomes express thousands of circRNAs from diverse genomic locations from coding and non-coding exons, intergenic regions or transcripts antisense to 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs). In addition to binding miRNAs circRNAs could function to store, sort, or localize ribonucleotide biding proteins (RBPs).

Eric T. Kool in 1996, 17 year ago, reported in the journal “Annual Reviews in Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure” the synthesis of both circular DNA and RNA oligonucleotides as useful biological tools and potential therapeutics. The paper discusses synthetic methods to prepare circular oligonucleotides as well as the effect RNA versus DNA on the backbone of the formed helices and the stability and half-live of these molecules in human serum. Furthermore, the paper reported that small circular oligonucleotides can encode information by serving as a template for polymerase enzymes and that rolling circle synthesis can be used to form long DNA and RNA multimer strands using these circular molecules as catalytic templates.

Seidl and Ryan in 2011 published a paper in which they showed how to use circular single-stranded DNA templates as synthetic DNA delivery Vectors for the production of miRNAs in human cells that express the proper RNApolymerases.

Proposed functions of circRNAs

Circular RNA appears to have the following functions:

- Bind miRNAs

- Store miRNAs as well as ribonucleotide biding proteins (RBPs)

- Sort miRNAs as well as RBPs

- Localize miRNA as well as RBPs

Whatever their function, more research in the future will hopefully more clearly define how these RNAs function. However, in recent years it has become increasingly clear that the cell can use a myriad of ways to process and stabilize RNA molecules.

Caged circular antisense oligonucleotides can be used to modulate RNA digestion and gene expression in cells

Wu et al. in 2012 report the chemical synthesis of 20mer caged circular antisense oligonucleotides. The researchers used the circular oligonucleotides to test their usefulness to perform photomodulated gene expression using ribonuclease H and non-enzyme antisense strategies. A photomodulated expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in HeLa cells to test the efficacy of the approach was used for this. Their results showed that the three synthetic caged circular antisense oligonucleotides containing 2’OMe modified RNA and phosphorothioate modifications were capable of photoregulating GFP expression in cells.

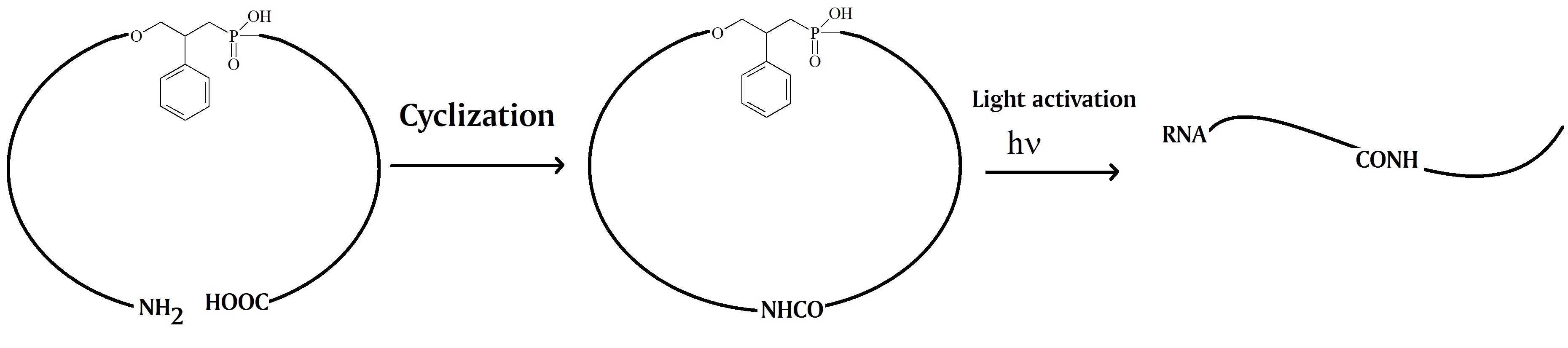

The oligonucleotides were synthesized using two 10mer oligonucleotides. A photocleavable linker and an amide bond linker were inserted between the two nucleotides to form the circular construct. The 3’-end of the linear oligonucleotide was modified with an amine group and the 5’-end contained a carboxylic acid group. After cyclization by forming an amide bond the caged circular oligonucleotide can be photo-cleaved in the middle of the previous linear oligonucleotide. The key feature is the resulting linear oligonucleotide strand that can hybridize with the complementary target RNA with the flexible linker in the middle.

The scientists argue that this strategy can overcome the problems observed for cleaved caged moieties or inhibitor strands used in earlier studies. One interesting finding reported was that the size of the ring of the caged antisense oligonucleotide is the most important factor to enable photomodulation of target RNA digestion by ribonuclease H. Furthermore, the research group proposed that this design may help to minimize the binding of caged circular oligonucleotides with target sequences due to the non-base linkers present in the circular oligonucleotides. However, upon light activation, the binding ability can be restored.

The same research group used caged circular morpholino oligomers to photo modulate β–catenin-2 and no tail expression in zebrafish embryos.

Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides have been used in the past, however, it has been noted that their use can generate misleading results. Eisen and Smith in 2008 discussed in their review published in the same year year how the use of morpholinos can lead to misleading results, including off-target effects.

The main observed difficulties encountered in interpreting experiments using morpholino oligonucleotides are as follows:

- The effectively of the knock-down is hard to determine;

- The possibility of “off-target” effects has to be addressed as well;

- it can be difficult to inject precise and reproducible volumes of morpholino oligonucleotides.

It is expected that the use of caged circular antisense oligonucleotides will help to block protein translation through a non-enzymatic antisense strategy. The researchers further suggested that the circular oligonucleotides could be made more functional by using other artificial nucleotides, such as bridged nucleic acids (BNAs).

Reference

BSI Blog: http://blog-biosyn.com/2013/09/11/what-are-circular-oligonucleotides/

Judith S. Eisen and James C. Smith; Controlling morpholino experiments: don't stop making antisense. May 15, 2008 Development 135, 1735-1743. Review.

Thomas B. Hansen, Trine I. Jensen, Bettina H. Clausen, Jesper B. Bramsen, Bente Finsen, Christian K. Damgaard & Jørgen Kjems; Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 495, 384–388 (21 March 2013) doi:10.1038/nature11993.

Kool ET.; Circular oligonucleotides: new concepts in oligonucleotide design. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:1-28.

Sebastian Memczak, Marvin Jens, Antigoni Elefsinioti, Francesca Torti, Janna Krueger, Agnieszka Rybak, Luisa Maier, Sebastian D. Mackowiak, Lea H. Gregersen, Mathias Munschauer, Alexander Loewer, Ulrike Ziebold, Markus Landthaler, Christine Kocks, Ferdinand le Noble & Nikolaus Rajewsky; Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 495, 333–338 (21 March 2013).

Enrique Pedroso, Nuria Escaja, Miriam Frieden, Anna Grandas; Solid-Phase Synthesis of Circular Oligonucleotides.Methods in Molecular Biology Volume 288, 2005, pp 101-125.

Martin Tabler and Mina Tsagris. Viroids: petite RNA pathogens with distinguished talents. TRENDS in Plant Science Vol.9 No.7 July 2004.

Seidl CI, Ryan K; Department of Chemistry, City College of New York, New York, New York, United States of America. PloS onedoi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016925.g001.

Yuan Wang, Li Wu, Peng Wang, Cong Lv, Zhenjun Yang and Xinjing Tang; Manipulation of gene expression in zebrafish using caged circular morpholino oligomers. Nucleic Acids Research, 2012, Vol. 40, No. 21 11155–11162 doi:10.1093/nar/gks840. http://dev.biologists.org/content/135/10/1735.full

Wu L, Wang Y, Wu J, Lv C, Wang J, Tang X.; Caged circular antisense oligonucleotides for photomodulation of RNA digestion and gene expression in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 Jan 7;41(1):677-86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks996. Epub 2012 Oct 26.

-.-